I’m dropping the “Age of Deuterogamy” tag, though it applies to this batch of movies. What we really notice here, though, is the emergence of Boomer identity, the uneasy aging of the 60s generation into 80s Yuppiedom, and the love-hate relationship with California.

One Trick Pony (1980)

This is a great rock music movie, a modest, affectionate, wonderfully-filmed look at the transition from the 1960s to the 1980s through the character of musician Jonah Levin—played by Paul Simon, who wrote both the script and (of course) the exquisite soundtrack. Levin hit it big in the late 60s with a Viet Nam protest anthem, but today he scrapes together a living on the road with his band, their new work dismissed by smarmy record executives played deliciously by Lou Reed and Rip Torn.

Simon’s character is going through a divorce that he doesn’t want, but his wife (Blair Brown) wants him to settle down and get a steady job. They have a little boy, and the father-son scenes are tender, calling to mind Kramer vs. Kramer. As an actor, Simon is just adequate. It seems his famous deadpan is no pose: he really has no facial movement. He looks good with his shirt off, though, which is not something I would have expected.

His script is often dynamite, even with the movie cliches about artistic integrity versus the pressures of the market, right down to Levin’s affair with the rich producer’s wife (a luminous Joan Hackett). But the plot doesn’t really matter: this is a loving look at the music life, with wonderful small parts and cameos, from Harry Shearer to Tiny Tim. Director Robert Young, who also directed Rich Kids, knows how to whisper.

Most affecting are a number of individual scenes: Simon in a bathtub with a waitress who belts out Janis Joplin; Simon’s performance of “Soft Parachutes,” which in the movie is presented as his late-60s draft protest song. The lyrics are bad (“villages burnin’”) but the introverted melody and somber filming makes it a comment not on Viet Nam, but on the generation that now finds itself retrospective, not cutting-edge.

Indeed, the movie is worthwhile just for one stunning shot in which we see both sides of a wall at a music club, with the B-52s performing “Rock Lobster” in the hall, and Simon’s band, the opening act, unwinding wearily in a changing room. Kudos to cinematographer Richard Bush, for this powerful, intricate visual announcement that the 80s have arrived.

A last note about One Trick Pony: it’s subtly haunted by Carrie Fisher. The Blues Brothers came out the same year, with Fisher as a vengeful former fiancee. Fisher was romantically involved with both Blues Brother Dan Ackroyd and Simon at the time. In One Trick Pony, Sam & Dave perform “Soul Man,” which seems to one-up The Blues Brothers, while in other scenes in One Trick Pony we see The Blues Brothers on a movie marquee, as well as a cinema window devoted to The Empire Strikes Back, which of course starred Fisher as Princess Leia. She and Simon married in 1983 and divorced the following year.

Foxes (1980)

Foxes is a grittier, sadder precursor to Fast Times at Ridgement High—it even has Robert Romanus warming up his Damone character—and part of a series of teenage wastelands from Kids to Euphoria. When first in development, the concept was to adapt Little Women to suburban Los Angeles. There are four high school girls, and a 16 year old Jodie Foster as the motherly Jo of the group, but otherwise not much Louisa May Alcott among the drugs, sex, and cutting school to slum around Hollywood.

Decidedly of its cusp-of-the-80s cultural moment, the movie has KISS posters, lots of feathered hair, designer jeans and belts worn over shirts, and Scott Baio on the first skateboard I can recall in a movie. Donna Summer’s “On the Radio” is the movie’s leitmotif, with a spot of Boston’s “More Than A Feeling,” and a Georgio Moroder synth soundtrack.

Jodie Foster is mesmerizing. She carries the movie, but unfortunately has to do so mostly uphill, given the film’s mix of pathos and cold voyeurism (this was Adrian Lyne’s first feature film), and the variability of the cast. Especially towards the end, the movie devolves into soap opera. But even here, there are moments of sharp pathos and icily powerful photography, as when Cherie Currie, lead singer of the Runaways but not much of an actress, is brought into the emergency room after a car accident and the respirator over her nose and mouth suddenly blooms with her blood.

Foster’s parents are divorced. Her father (Adam Faith) is a wealthy music producer who conducts a well-meaning if ineffectual dad-daughter talk backstage at a rock concert. Sally Kellerman plays the fragile mom, who needs Foster’s supervision as much as Foster’s teenaged friends do. Their relationship is the heart of the movie, but it doesn’t come off mainly because Kellerman can’t keep pace with Foster’s acting. The latter is flawless, while Kellerman seems like she’s trying to channel Hepburn in Stage Door or Swanson in Sunset Boulevard.

Foxes is a diffuse admission of how horrendous the Californian enlightenment had been, especially to vulnerable young women, and so, despite its teenaged cast, it is an example of the emergence of Boomer identity in these movies of 1980. If Paul Simon in One Trick Pony tries to keep the old band together, Foxes shakes its head over what the new generation is up to.

It doesn’t formulate a coherent answer, and Foster at a few points is forced to mouth speeches of Boomer disillusionment. I was reminded of Michael Walker’s ultimately disappointing history of Laurel Canyon, which chronicles a chilling level of crime and moral depravity, but still clings to the self-exculpating 1960s legend of California being wonderful until somehow, for some reason (Walker blames money and cocaine), the buzz got harshed.

The Last Married Couple in America (1980)

Divorce movie veterans George Segal, Richard Benjamin, Natalie Wood, and Valerie Harper have fallen low indeed in this reheated “the counter-culture is ruining our marriage” comedy. This is a film from 1980 in which the characters use the phrases “the sexual revolution” and “the New Morality” as if they’ve been cryrogenically frozen for 15 years. At one point, the children are watching a cowboys and Indians show on a black-and-white TV, at a time when The Dukes of Hazzard and Magnum, P.I. were on. It’s bizzare.

Every cliché, stale even in the 1960s, about the vanishing of traditional marriage is trotted out here. “Divorce is one of America’s biggest growth industries,” one swinger announces. His run-down of marriage continues: “As an institution it’s antiquated. It hasn’t been updated in 2000 years.” Neither has this screenplay.

Well, there are a few updates. A gay couple is presented as the only successful relationship among the friend group. It’s a gag, but not entirely. The sexual content is more explicit too. If your idea of comedy is to hear Valerie Harper talk about having her vagina tightened, Richard Benjamin complain about erectile dysfunction, and George Segal learn he has contracted gonorrhea, this is your movie.

The climax is the predictable scene in which Segal and Wood as separating husband and wife show up at the same party with their much younger dates in order to make the other spouse jealous. (This was already icky when Bob Hope and Jane Wyman did it in the 1969 How To Commit Marriage.) We get the same lame and joyless party from every counterculture sex comedy. In this case, Dom Deluise tries to convey libidinous excess but comes off like a high school theater teacher on speed.

Things get dark when a couple in an open marriage try to entice Segal and Wood into a swap, and it becomes clear that the husband is just pimping out his wife. Segal and Wood refuse the swap, and the wife suddenly realizes how degraded her existence is. “I don’t even know what making love or marriage means anymore!” she cries before walking out on the sleazy husband. Segal and Wood realize they love each other and, despite the blandishments of the “New Morality” (whether circa 1964 or 1980), are happy in their traditional marriage.[1]

As I said, this is yet another painful throwback to the marriage vs. counterculture film. Wood had already gone down the near-swap road with vastly more emotional impact in Mazursky’s brilliant Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969). I was surprised to see such a dismal retread, but then I realized that I shouldn’t be: the marriage vs. counterculture movie is really just a variation of one of the oldest and sturdiest of Hollywood marriage plots: the separation-and-reunion (sometimes divorce-and-remarriage) plot, which goes back to the silents. Add to this the generational angst of the Boomers over their lost youth, and it makes sense that these tropes have become chronic cinematic reflux.

Credit to The Last Married Couple in America for at least acknowledging how arbitrary whatever the latest iteration of the “New Morality” is. Richard Benjamin attempts to tell his friend Segal why he’s getting a divorce:

Benjamin. “Police strikes, women’s lib, gay lib, condominiums.”

Segal. “What does that got to do with your marriage?”

Serial (1980)

Despite its interesting cast, including Christopher Lee as a corporate exec named Stu Luckman who spends his off-hours riding with a biker gang under the name “Skull,” Serial is both cartoonish and rancid. The screenplay is based on Cyra McFadden’s satirical column, published in book form in 1977, about Marin Country, a Bay Area culture that had made the trek from hippiedom to yuppiedom without skipping a beat or a yoga class. Psychobabble, radical acceptance, affluent hypocrisy, guilty reliance on a servant class, hypersexuality and its attendant miseries, cocaine, preening environmentalism—it’s all here. To a great extent, so are we.

Martin Mull and Tuesday Weld are the normies whose marriage buckles under the assaults of psychotherapeutic fads, omnipresent sexual exhibitionism, the baroque rituals of white guilt, and any number of other left coast plagues. Like George Segal and Natalie Wood in The Last Married Couple in America, they are already outliers, not having been previously married and divorced. A conversation between two commuters on the ferry Mull takes to work runs as follows:

“Who’s the chick?”

“Martha Sterns.”

“I don’t know her.”

“She used to be Martha Byers.”

“No, I’m not familiar.”

“And before that she was Martha Krimm.”

“And before that Martha Peale?”

“You know her!”

“I’m Fred Peale.”

“Right! Her first husband.”

“No, her second.”

As in all such movies, Mull and Weld separate, sow their wild oats, and then get back together at the end, voicing lessons learned about the dangers of too much freedom. They rescue their daughter from a cult, which is played for laughs but creepy given the frequency of such things in that locale.

But the real turnaround comes after Mull’s friend, the very Jewish Sam (Bill Macy), also eats from the tree of Bay Area freedoms. Sam leaves his wife, grows a beard, takes up with a 15 year old supermarket check-out girl, and—burns out. An empty shell, addicted to psychotherapy and Quaaludes, he stares listlessly over the ferry rail, and jumps to his death.

His funeral includes a Native American drum ceremony, but Mull can’t endure the New Age nonsense laid over the memory of his friend. “I loved him!” yells Mull. “I loved the way he loved his stinking cigars, and that big dumb car of his, and the Johnny Carson show, and the broads with the big tits! Can you relate to that?”

It’s a pathetic little speech. I can’t find it in the McFadden original. I take it to be a kind of outcry from a certain segment of Jewish Hollywood that reflected the counterculture in movies but was never really comfortable with the pagan excess of it all. But then, if all you have for a tradition is cigars, Johnny Carson, and “big tits,” you can’t be too surprised when the kids join cults—or the parents snort coke and collect new spouses.

At the end of the movie, Mull decides he’s had enough of Bay Area insanity and will move his family to Denver. But the message is not that they are escaping California, but that they are helping to export California to the rest of the country. Even the conservative President elected that year was an export.

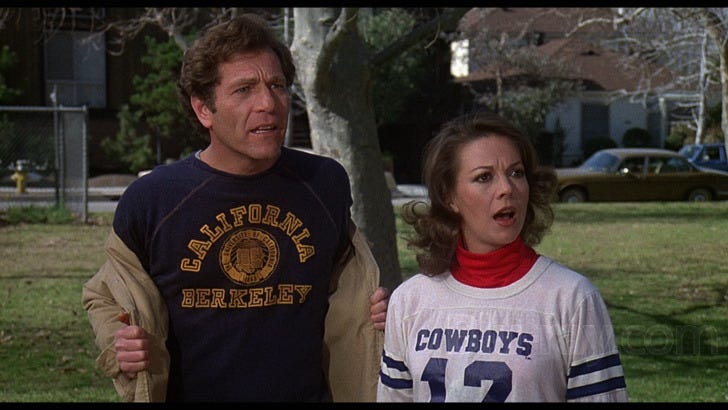

Coast to Coast (1980)

In this romantic comedy, Dyan Cannon has been forcibly committed to a mental institution by her husband so that she can’t divorce him and take half the estate. She escapes and hitches a ride with trucker Robert Blake. She cajoles and connives him into taking her across the country in his rig, back to her mansion so that she can bring her husband to justice.

Coast to Coast thus belongs to the trucker film genre that took off in the late 1970s with hits like Smokey and the Bandit and Every Which Way But Loose, but here pairs the ne’er-do-well cowboy Blake with Jewish-American Princess Cannon. Comparisons to the same year’s Private Benjamin with Goldie Hawn are apt.

At the end, Cannon literally crashes a party her husband is throwing for all their friends at their mansion—driving a cattle rig through the place. The smash-up is impressive, though one feels for the fictional animals. Amidst the wreckage, she asks her enraged husband: “Now, can I have a divorce?”

Big rigs aside, the movie is an attempt to repeat It Happened One Night, with a lovable scoundrel accompanying a spoiled princess on an involved road trip back to her husband, and the two falling in love along the way. Coast to Coast is a reminder of how delightful Cannon is but, despite the charisma and energy she and Blake each bring to the picture, they don’t have a good script to work with. Capra’s 1934 vessel is filled here with fistfights in various pigsties and livestock pens.

[1] More disturbing is that you realize at the end that the Segal and Wood’s young children have been asleep in the house during the party. Hollywood generally posits unrealistically somnolent children, but it’s still a shock.