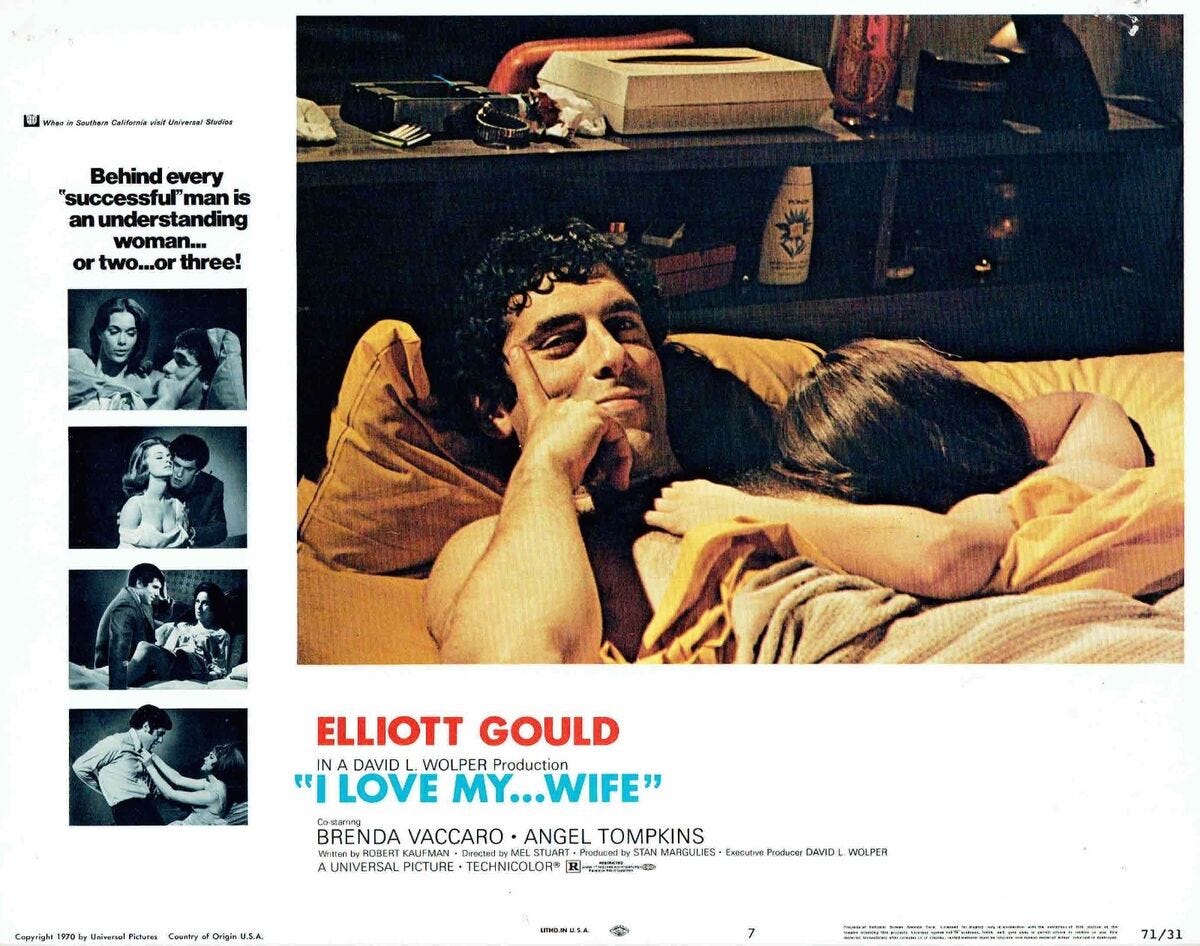

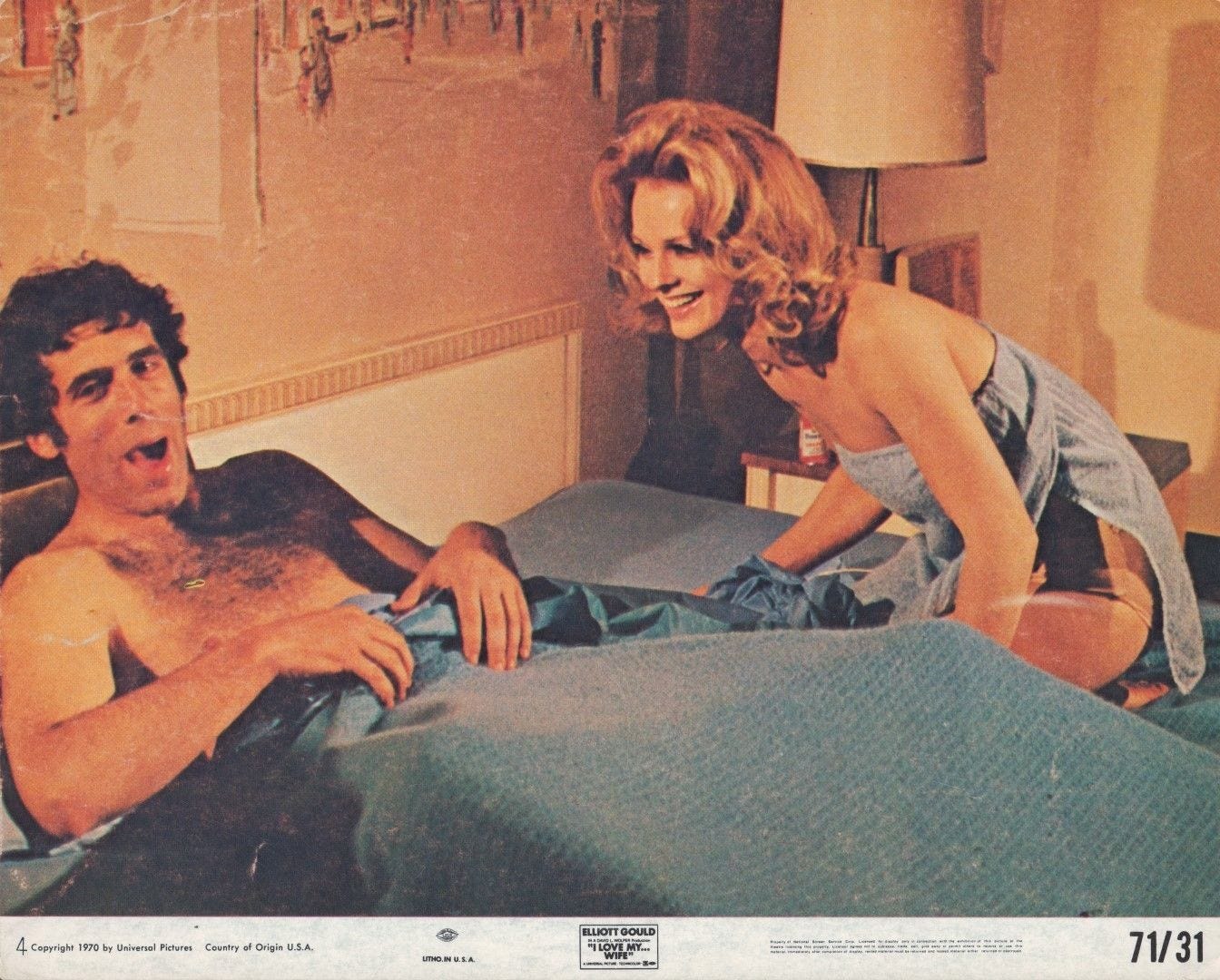

In I Love My Wife, Elliott Gould plays a successful surgeon, married with kids, who grows dissatisfied with married life. He becomes a serial philanderer, screwing every nurse in every hospital he works in. He finally meets the woman of his dreams (knockout Angel Tompkins). She is married and at first turns him down, but he pesters her relentlessly with righteous, zeitgeisty selfishness. “It’s America. It’s 1970,” he opines. “You’re married, living in the same craziness I am. How can you be happy?” He beds her, they agree to divorce their spouses, but he gets cold feet after she goes first.

Having made a shambles of both their marriages, he further degrades his wife (Brenda Vaccaro) by insisting she remake herself in the name of marital therapy. He enrolls her in fat camp, art classes, psychoanalysis. In the end, but not soon enough for the viewer, both Tompkins and Vaccaro banish Gould from their lives. We leave him in a singles bar where he is picking up a stewardess.

This is all played for sleazy laughs, though never funny, and with half-hearted pretentions of being social satire—which all makes sense, as the screenwriter is Robert Kaufman, who also gave us the same greasy sensibility in Divorce American Style. From Divorce American Style too is a scene in the marital bathroom with the wife using a Waterpik and gargling, intended to tell us that the familiarity of marriage is an inevitable libido-killer.

More pronounced here is the earlier film’s uncomfortable obfuscation of a certain kind of sociological Jewishness. In I Love My Wife, we see the protagonist early on as an adolescent being launched toward a lifetime of sexual compulsion by a neurotic mother who, for instance, pounds on the bathroom door to make sure he isn’t masturbating. (He is.) It’s all third-rate Portnoy’s Complaint, yet we then see the family at . . . church?

We can see plainly that they are Jews, like the director Mel Stuart; the screenwriter Kaufman ; Gould, married for a decade to Barbra Streisand; and, it goes without saying, the producers. The Gould-Tompkins affair is something of a Golden Shiksa redux, also out of Roth. So why this bizarre pretense that Gould and family are Protestants?

The answer is that I Love My Wife is one of many movies from 1967 to 1972 that stumble awkwardly around the question of how to present overtly Jewish characters, especially men. With painful insecurity, and using the license of the counter-culture to overcompensate with aggression and offense, these movies gave us a rogues gallery of often profoundly unlikeable characters—though a few are sympathetic anti-heroes.

Film critic J. Hoberman calls them the “Nice Jewish Bad Boys”: “(mainly) young, (sometimes) neurotic, and (by and large) not altogether admirable Jewish male protagonists cut off from their roots but disdainful of white-bread America.” The fact is that most of the Jews of Hollywood were at that time the last ones capable of thoughtful, aesthetically compelling, historically informed, sociologically self-aware portrayals of Jewishness. Their own sort tended to be conflicted, shallow, attenuated, and touchy.

As Hoberman notes, this cinematic moment mostly vanished by 1973, though the wise guy, anti-WASP figure, schlemiehl or hero, would occasionally resurface even in the twenty-first century. Some of the films of this wave sublimely transcend their cultural dead-ends (e.g., The Heartbreak Kid), but I Love My Wife is not one of them. And the trio of actors most associated with the Nice Jewish Bad Boy—Elliott Gould, Richard Benjamin, and George Segal—never recovered the cache they had as actors after the 1970s.

The gangly Gould is by far the most puzzling of the three. With his broken-reed woodwind voice, slack lower lip, hairy yet forceless body, and mama’s boy speech patterns, it is hard to see how he was taken as a leading man, even a kind of sex symbol for a brief moment. Those of my age (Gen X) and younger know him as the very bourgeois father of Ross and Monica Geller in Friends and the swishy Reuben Tishkoff of Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Eleven. Those roles fit. Yet half a century ago Gould was sold as a sexy Jewish everyman for the counterculture.

But this happened at a time when Jewish Hollywood wasn’t sure what a male Jewish sex symbol ought to be (it may still be unsure), while Gentile America seemed willing to try out most anything in good faith. The article accompanying his September 1970 Time magazine cover (“Star for an Uptight Age”) is one extended expression of embarrassed surprise that this nebbish is perceived by some as hip.

In fact, he had just landed the lead in an Ingmar Bergman movie, The Touch (1971), in which he draws the married Bibi Andersson away from her husband Max von Sydow. The Touch is a curious movie, not a good one. There is fretful intensity but no chemistry between Gould and Andersson, and it is never made comprehensible why Andersson is attracted to him, physically or emotionally, unless she is acting out some masochistic dysfunction for reasons not introduced in the movie. Gould’s character is petulant and demanding. He strikes Andersson, but it is the sudden lashing out of a hysterical child; she is not afraid or even angry, just amused.

Yet Gould’s performance as a Jewish archeologist whose family was murdered in the Holocaust, and Bergman’s (and his cinematographer Sven Nykvist’s) honest attentiveness to their imported American, lets us study the combination of man and boy Gould is. Though 6’ 3”, his characteristic position in the film is to place his head in Andersson’s lap, a little boy seeking maternal love.

Sex symbol? Hardly. But it clarifies wherein the flashes of Gould’s elusive charisma reside, and this is, strangely, precisely in his projection of mama’s boy niceness.

We see this in his and director Paul Mazursky’s 1969 breakout film, Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice. (The brilliant Mazursky understood Jewishness and understood the counter-culture, and so could explore both rather than unintentionally enact them.) It is of course hilarious when the other three leads are commencing their orgy and Gould is still in the bathroom topping up his deodorant and checking his teeth. But the real Gouldian moment is when, in response to the proposed swinging session, and against the crushing weight of the entire counterculture, Gould says, sadly and simply: “It just seems wrong.”

At such a moment he is not too soft for the world. He is a rebuke to the world for being so hard. But who besides Mazursky would allow for such a moment, for American Jewishness not as neurosis or anti-establishment politics, but as that little spot of decency around which God’s world turns?