The Four Seasons (1981)

The Four Seasons is quite negative about divorce. The comedy-melodrama follows three married couples over the course of a year, focusing on what happens when one couple (Len Cariou and Sandy Dennis) divorces and the ex-husband takes up with a new, much younger girlfriend. Alan Alda directed and stars in it, with Carol Burnett playing his wife. Before the marital break, Alda toasts to the three couples’ friendship and the loyalty and values that enable them to “huddle against the cold winds of divorce that have blown through the lives of our friends.”

Alda is aghast when he learns that Cariou is divorcing Dennis. The end of this marriage banishes a shattered Dennis from their friend group, sends ripples of anxious self-questioning through the other couples, and plunges Cariou’s college-age daughter (played by Alda’s real-life daughter) into a depression. It is heartbreaking to see Beatrice Alda shuffling around zombie-like during what is supposed to be a fun family soccer game. “Smile, goddammit!” Cariou yells at her, frustrated that his own new happiness is not transferable to his child. We also learn that Cariou’s character had been having affairs all along, and that his own parents were divorced. It seems pertinent to note that Alda is one of those Hollywood rarities who married once and has stayed married, for 67 years and counting.

And yet, the movie finally leaves the dark elements of divorce to the side, proceeding to a pleasant enough ending, ensuring box office success by keeping things winsome. The movie title and its soundtrack come from Vivaldi, after all, not Schoenberg. Alda “loses control” in the final melodramatic scene, which means that he throws a cup and pulls a stuffed moose head off the wall of the ski cabin, before apologizing.

A mark of the movie’s popularity is that it spawned a short-lived TV spinoff in the early 1980s. A mark of our cultural impoverishment today is that the movie was remade this year as a TV series, with one of the couples inevitably made same-sex. To judge from the trailer, the remake looks as if it were written and created by AI, operating under instructions to make the characters as interchangeably repugnant as possible.

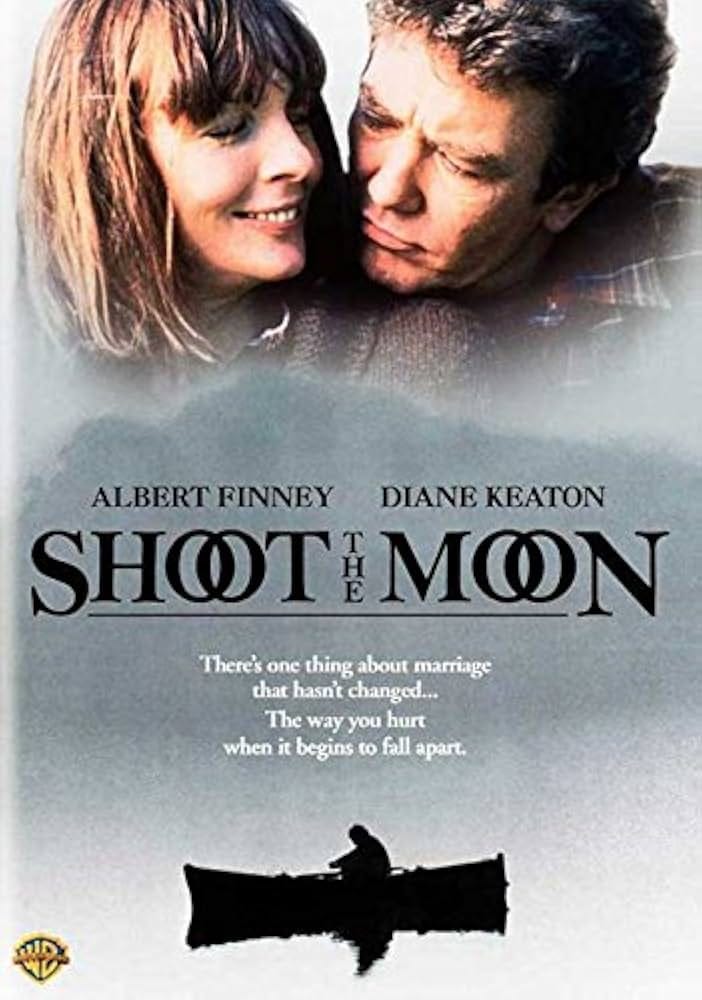

Shoot the Moon (1982)

After Two For The Road and Shoot The Moon, Albert Finney has left his cinematic mark as deeply unpleasant husband. In the former he snarls for two hours at Audrey Hepburn. Here, he is a celebrated author who makes his wife (Diane Keaton) and four daughters miserable prior to and after the formal separation. There is a lot of noise, broken-down doors, and smashed crockery in this movie, and at the end Finney drives his car through the home additions Keaton’s new boyfriend has built for her.

Despite a few fine scenes, though, the family misery isn’t very illuminating. Much of the movie has to do with the family house, an actual farmhouse which the filmmakers had dismantled and reassembled on location. They may have hoped that the authenticity of the home would deliver the movie—but too much else in the movie feels forced, the motivations obscure. The happiness once shared by husband and wife is only indicated late in the movie, too late to kindle our sympathy for them.

What emerges most affectingly in the course of the movie is the impact of the divorce on the children. We witness the girls’ confusion and anger, and also their strong little trooper spirits. When they first meet their father’s new girlfriend we see the discomfort on their faces—they wish they could be anywhere else—but also how they put on a cheerful demeanor for their father’s sake. The movie stumbles but, at its best, highlights the disjuncture between what divorce means for the parents and what it means for the children.

The Big Chill (1983)

There is divorce in The Big Chill, but it’s hard to keep track of, given the elastic definitions of marriage that we witness among the narcissists assembled here. Gathered for the funeral of their college friend who killed himself, the characters spend their time doing drugs, filming and then watching themselves on a home movie camera, and making acerbic quips at each other. The only whiff of decency in the movie is the dull husband who departs to go home and take care of his kids. We’re meant to frown on his uptight ways, but he’s not wrong when he criticizes the selfishness of the rest of the group’s notion of life: “The thing is, nobody said it was going to be fun. At least, nobody said it to me.”

The characters’ narcissism is embodied most infamously in, first, the friend (Mary Kay Place) who, evidently too busy with her career as an attorney to find a husband, has shown up at the funeral determined to get impregnated by one of the men so that she can be a single mother by choice and, second, in the married couple played by Glenn Close and Kevin Kline, who enable their friend’s selfish decision. Even in Fatal Attraction, Close never looked so much like a grinning sociopath as when she pimps out her husband and his sperm.

Note: I have written on a divorce-and-remarriage movie from this period that I love, Paul Mazursky’s Tempest.