The Way We Are

The Way We Were (1973) is a deceitful, even repugnant, movie. In it, characters played by Barbra Streisand and Robert Redford meet in the 1930s in college, fall in love when they reencounter each other during WWII, get married, and divorce in the 1950s against the background (and to some extent because) of the Hollywood Blacklist. The movie purports to be a love story, but rather than love it shows the narcissism of Streisand’s character as she browbeats Redford’s. It seems at first to be an encounter between the different cultural worlds of Jew and WASP, but it is instead a two-hour revenge by a Jewish stereotype on a Gentile stereotype, with no more truth than a Punch and Judy show. It pretends to be a tale of moral commitments, but it is a smarmy apologia for a particularly nasty politics.

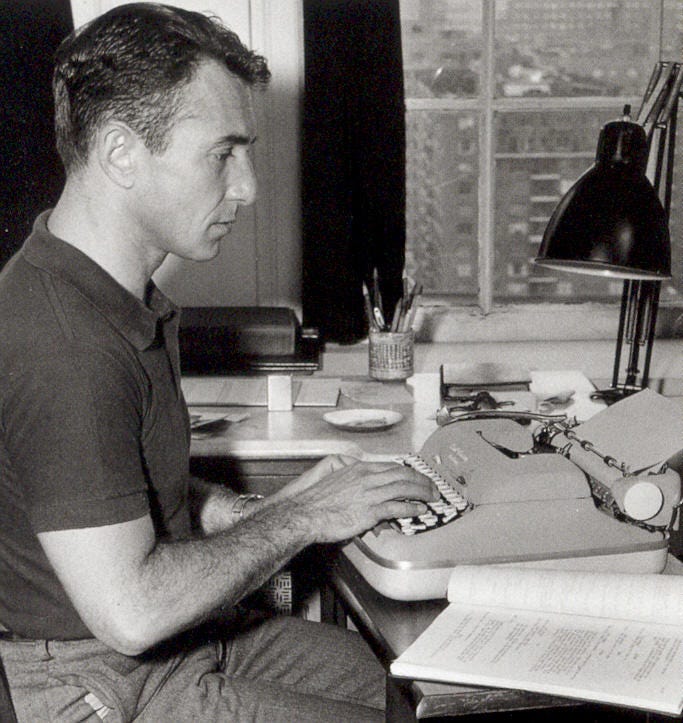

During a twenty-minute flashback introduced by the movie’s wistful title song, Streisand’s Katie Morosky, a Jewish member of the Young Communists League, crosses paths with classmate Hubbell Gardner at a version of screenwriter Arthur Laurents’ alma mater, Cornell. Redford’s Hubbell is athletic, wealthy, blonde, blue-eyed, sociable. His talents do not seem to express themselves via effort but rather by nature. Streisand must work to pay her way through college, while Hubbell letters in sports, attends parties, and pulls pranks. Streisand is perpetually outraged, banging out articles on a typewriter below a portrait of Lenin, yet it is Redford who wins the praise of their writing instructor for his short story “The All-American Smile,” which begins: “In a way, he was like the country he lived in. Everything came too easily to him.”

Their relationship is presented as an encounter between Jew and WASP, in a movie that arrived at the tail end of Hollywood’s late-60s, early-70s anxious cinematic obsession with Jews and Gentile America. In 1967, the makers of The Graduate hoped to cast Robert Redford as the lead and only with great hesitation considered the Jewish-looking Dustin Hoffman. Six years later, Redford’s classic American handsomeness and its contrast with Streisand’s Jewish looks would be a defining feature of The Way We Were, from the way the camera (and Streisand) ogles a uniformed Redford at the bar, to Streisand’s telling Redford: “I’m not attractive in the right way.”

The Jew vs. WASP motif sounds throughout the movie. Streisand mistakenly offers a hungover Hubbell a Jewish breakfast of smoked fish, herring and onion, and pickles. She jokes with him about the impossibility of naming their daughter after Katie’s grandmother, Rokhl. With Hubbell’s Park Avenue social circle and Streisand’s hardscrabble origins adding a class divide to the ethnic-religious ones, this is a variation of what the Jewish mother cautions in more oblique fashion in the 1956 film The Benny Goodman Story, when her son falls in love with a well-to-do blonde Gentile: “Bagels and caviar don’t mix.”

Yet Redford’s WASP is never more than a prop, a target for the projected resentments and desires of Streisand’s character and, through her, the screenwriter. Arthur Laurents, who was gay, admitted late in life that he based Katie Morosky on himself and that Redford’s character reflected the boys he had a crush on in college.[1] Redford’s Hubbell is beautiful to look at—a “fantasy WASP,” as Laurents called him—but he is not a person. The camera looks at him, from the bar scene mentioned above, to the scene in Streisand’s apartment when he is filmed with his back to us, i.e., through Streisand’s eyes, not from his own. And there is of course the scene of their first sexual encounter, with Streisand taking advantage of a drunk and passed out Redford.

This is not a relationship, even a failed one, and the movie is not a love story but a kind of triumphant victory lap over a defeated enemy. Streisand’s Katie may joke about naming their child Rokhl, but that is precisely what she does—in the American form of Rachel, at the end of the movie being raised by Katie and her new husband, David Cohen.

So much for the movie’s ethno-religious imagination. Where the movie is truly pernicious in its politics. The Way We Were was the first feature film to treat the Hollywood Blacklist, and it does so by serving up a simplistic moral fable in which politics is not about a clash of competing ideas and their consequences, but a battle between the good people who care (the left) and the bad people who don’t (the right).

Streisand’s character replaces Lenin’s portrait on her wall with those of Stalin and FDR, and we are given to understand that Communism is a sweet-natured idealism, completely compatible with American values of freedom and dignity. The people who oppose it are either fascists, lazy and indifferent, or dangerous mobs. Absent from The Way We Were is the reality of Soviet totalitarianism, its monstrous body count or its prison camps. Streisand’s Katie constantly claims to be standing up for the First Amendment and freedom of expression, in which actual Communists did not believe, and that was certainly not allowed in the Soviet Union.

Particularly dishonest is the scene in which the collegiate Streisand speaks out on the Spanish Civil War, a disgusting bit of Orwellian nonsense. She chides her fellow students for being “afraid” of Communists who, after all, only want “peace.” The scene also lets us know that what is really at stake is not the Communism of the 1930s, but the liberalism of the Boomer generation. Flattering her audience, she tells them: “You’re the best, the brightest, the most committed generation this country ever had.” This nod to the David Halberstam book that came out the year before the movie links the Spanish Civil War with Viet Nam and identifies Soviet Communism with Sixties idealism, all in a haze of boomer self-congratulation that would characterize Hollywood’s treatments of Communism and its own romance with it ever since. (Thank goodness for exceptions like Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront and the Coen Brothers’ Hail, Caesar!)

The Way We Were is a movie of continuing relevance for us in two unfortunate ways. First, it crystalizes the left’s self-serving conviction that politics is really about compassion. The movie tells us that the earnest Streisand cares, while the genial Hubbell does not. “I guess there are just some things that are difficult for me to laugh about, Hubbell,” she says when he asks why she takes politics so seriously. When Hubbell’s conservative friends make jokes about the death of FDR she rages at these callous people “who tell stupid jokes instead of feeling something.”

Left out is the possibility that one might have feelings yet also be critical of FDR. (Katie does not seem to care about FDR’s internment of Japanese-Americans, for instance.) One might feel a great deal of compassion—for the victims of Communism. Indeed, despite the movie’s conceit that conservatives are callous and self-interested while progressives brim with love, Streisand’s Katie is a horrible person: fanatical, self-righteous, intolerant. She dismisses any dissent from her political views with easy slander: “fascist,” “reactionary,” “racist fink.” She is very much a picture of the viciously intolerant left then and now—in fact, what the actress herself would famously become. (Redford would say of the movie: “I also thought the politics in it was bullshit. It was knee-jerk liberalism and very arch.”)[2]

The second aspect of the movie that is still too much with us is its definition of Jewishness. The Way We Were understands Jewishness as a constellation of class, ethnic style, and—above all—left-wing politics. It moreover defines this Jewishness in opposition to an imagined WASP elite that is also a constellation of class, ethnic style, and politics. Much of mainstream American Jewish identity had by the 1970s morphed into this collection of political impulses and cultural holdovers from long-gone ethnic and class experiences. The results are still evident today, sadly, even as there is not much of a WASP culture left for American Jewish identity to shadowbox with.

In movies, the moth-eaten Jew vs. WASP template would be reused in comedies such as Meet the Fockers (2004), in which the Jews are played by Streisand and Dustin Hoffman, and the WASP patriarch is played, bizarrely, by Robert DiNiro. Hoffman’s character is of course a left-wing political activist, environmentally conscious, and comfortable with his bodily functions, in contrast to DiNiro’s rock-ribbed Republican who prefers privacy in the bathroom. Streisand here is a sex guru for the over 60 crowd, reflecting the way that, in the wake of the sexual revolution, American Jews reinvented themselves as sexually comfortable, open, and non-hypocritical—again in constrast to WASPs, who were imagined as being repressed and sexually dysfunctional. The stereotypes of The Way We Were repeat themselves again and again, and it is sometimes difficult to say what is tragedy and what is farce.

[1] Laurents’s ambivalences and self-deceptions are on display in his memoir Original Story By: A Memoir of Broadway and Hollywood (2000), which indicates the extent to which he used political activism as an outlet for personal unhappiness.

[2] Quoted in Tom Santopietro’s The Way We Were: The Making of a Romantic Classic which is, with Robert Hofler’s more critically engaging The Way They Were: How Epic Battles and Bruised Egos Brought a Classic Hollywood Love Story to the Screen, one of two books about the movie published in 2023.