Kramer vs. Kramer (1979)

Here we are. The big one. You’re writing about divorce in American film? You’re going to talk about Kramer vs. Kramer, right?

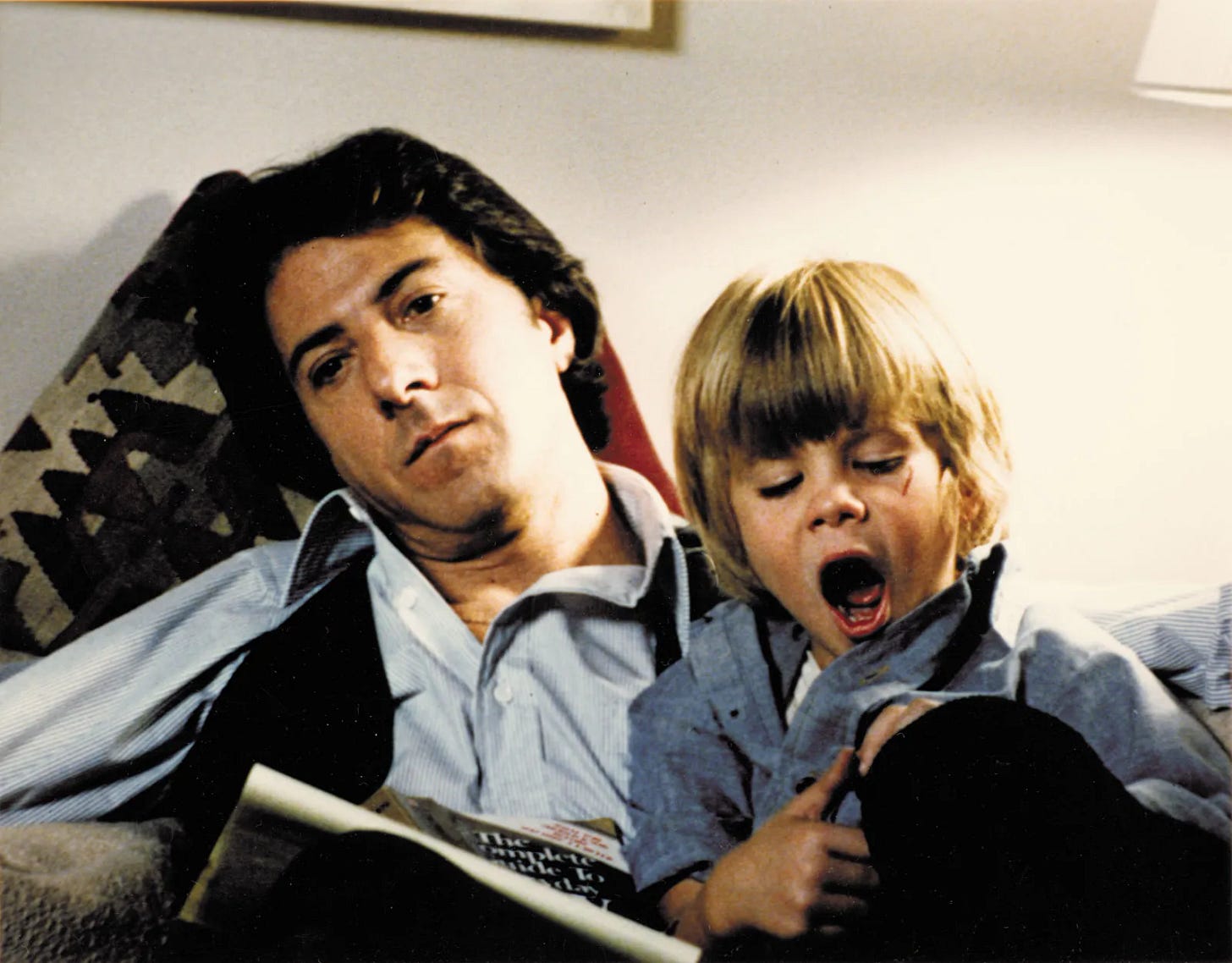

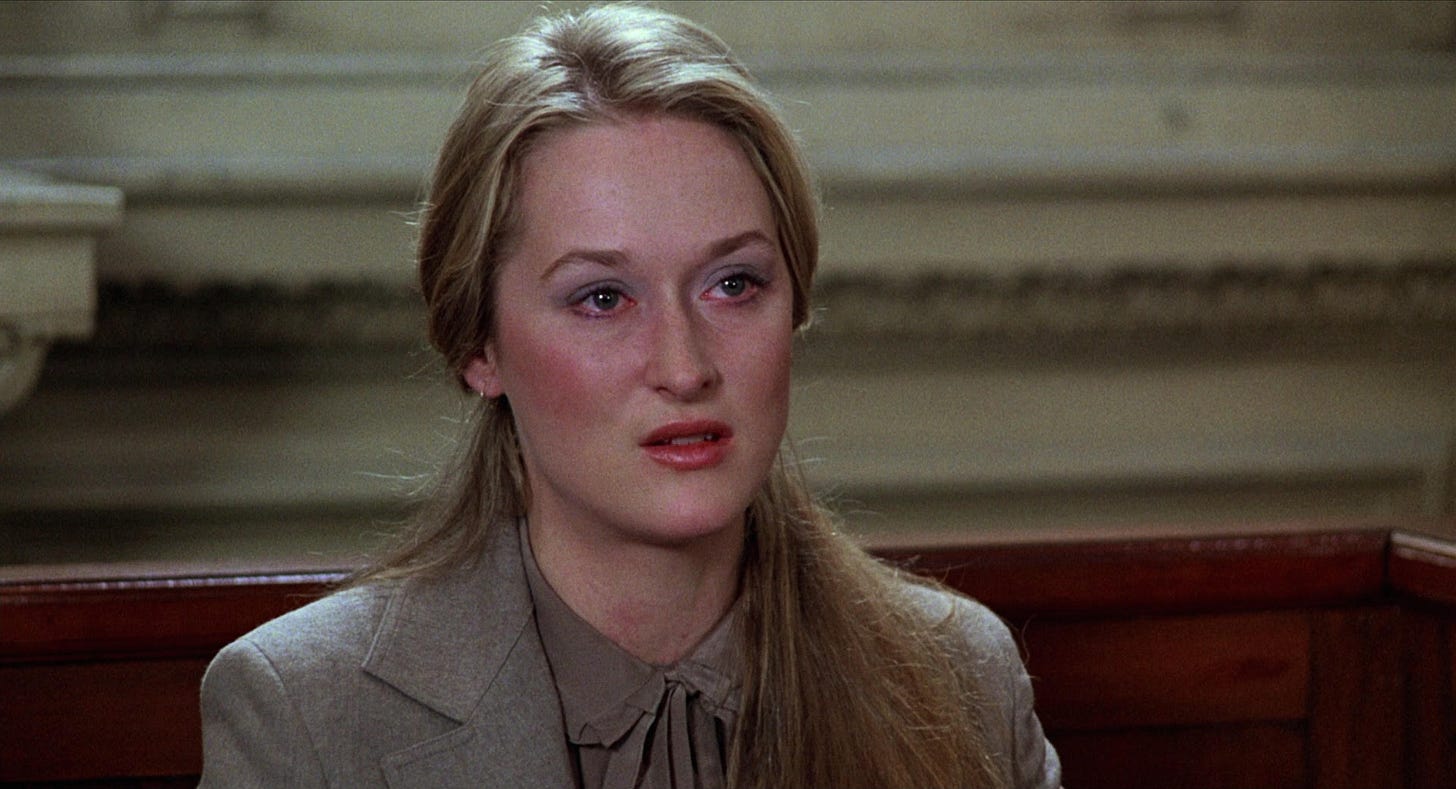

Absolutely. It’s a powerful film, deserving of its five Academy Awards for best picture, director, adapted screenplay, actor, and supporting actress. Nestor Almendros’s cinematography, and performances by the whole cast, from Oscar-winners Hoffman and Streep, to nominees Jane Alexander and eight-year-old Justin Henry, all helped make it the iconic (overused word, but appropriate here) American divorce movie.

Kramer vs. Kramer stands tall among the movies of what I have been calling the Age of Deuterogamy, like them focused not on reuniting the divorced couple, but on what happens after: in this case, the care and custody of their son, the transformation—redemption—of the father through his role as single parent.

Neither of these elements are absolutely new. Courtroom custody battles have been a staple of the divorce movie for generations. And even John Wayne played a single dad. Certainly, there are many other divorce movies that I like more.

But, scene by scene, Kramer vs. Kramer deploys the emotional resources of film with such overwhelming efficiency that other movies, and very good ones, are apt to seem baggy by comparison. What I will focus on here is how much the film owes to Robert Benton—not only as director but as screenwriter.

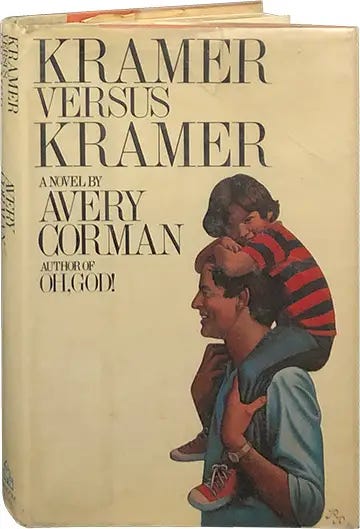

I’ll do this by discussing the Avery Corman novel on which Benton based his script, showing how Benton selected and elevated the source material. Corman’s successful first novel, Oh, God! had been adapted for the 1977 hit comedy with George Burns and John Denver. Producer Stanley Jaffe bought the rights to Corman’s third, Kramer vs. Kramer, and Benton, when attached as director-screenwriter, developed the script with important input from Streep and Hoffman.

Corman’s Ted and Joanna are both Jewish, well-off, though he has working-class Bronx roots while she’s from a more refined Boston family. Joanna, educated and having once commenced a career, is bored with her life as a wife and stay at home mother, but Ted is opposed to her getting a job. Her unhappiness mounts until she makes her break, forty pages into the book, leaving Ted and their son Billy. Benton begins the movie at this point.

To some extent, then, Corman’s novel is a take on feminism, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique written from the standpoint of the callous husband. Except that this is already 1977 and Ted himself recognizes that his dismissal of his wife’s professional aspirations is weird and retrograde. Ted seems less a chauvinist than simply shallow and oblivious, and Joanna in her own way is just as limited. After she leaves, Ted reflects: “Once, he was married to the prettiest girl at the party and somehow she got away, and now the party was dull.”

In any case, the book is less interested in the marriage that was than in the dynamics, economic and sexual, of post-marital dating. Two divorced people with kids at home are watching the clock as much as the other person:

The meter was running on both sides. He was paying for a sitter, she was paying for a sitter. At $2 an hour, it would cost them $4 an hour, total, just to sit there. Something big had to happen fast. . . . The logistics could begin to take precedence over the experience. This happened to Ted one evening when he was saying to himself, it’s 10:30, $6 in sitting. Do we stay or do we make love? If we make love, I think we should go in the next five minutes or it’s another hour in sitting, and he was short of cash that week.

Yet Ted needn’t worry so much, about the financial equation at least; in the book he has a wealthy brother who will front him whatever he needs, though Ted does not like to accept such help. Especially surprising in comparison with the movie, in which Dustin Hoffman needs to juggle work and childcare responsibilities, Corman’s Ted immediately hires a nanny. There is no French toast scene, as in the movie when a panicked Hoffman has to learn how to make breakfast for Billy. Weekends can be long and demanding, but here’s the weeknight schedule:

Ted was usually home near six; he and Billy would have dinner together, he would give him a bath, they would play for a while, Ted would read him a story, and somewhere around seven-thirty Billy went to bed. It was a fast hour and a half.

In fact, when Ted is laid off from work (this happens twice in the book), he does not stress over money, and does not spend any of his additional free time with his son.

One can’t entirely blame Ted. In contrast to the movie’s sympathetic Justin Henry, Billy in the book is a pill, without personality or novelistic substance. He mostly demands toys. Informed that he’ll see his mother again after her departure, he says, “Maybe she’ll buy me something.”

The touching and masterfully concise representation in the movie of Hoffman’s growth as a father and a human being, the love and trust that develop thereby between father and son, is told but not shown in the book. The night before Ted is to give up custody of Billy to his ex-wife, Corman has Ted reflect:

He was grateful for this time. It had existed. No one could ever take it away. And he felt he was not the same for it. He believed he had grown because of the child. He had become more loving because of the child, stronger because of the child, kinder because of the child, and had experienced more of what life had to offer—because of the child. He leaned over and kissed him in his sleep and said, “Goodbye, little boy. Thank you.”

In contrast to this strangely impersonal (“the child”) speech, Benton gives us a second French toast scene, father now a good parent, basking in the quiet approval of and communion with his son. (We parents are all, deep down, especially vulnerable to the approval of our children for our parenting.) The scene is far more convincing than Corman’s book, beautifully eloquent without a word of dialogue.

Similarly, the power of the courtroom scenes in which Hoffman and Streep, through facial expression, show that they have come to empathize with each other, to acknowledge the justice of the other’s claim to custody, and the extent to which they have worked to rise above their past failings, is in the novel just a moment of speculation on Ted’s part:

He could hardly recognize himself from the testimony. Yet he knew he had been that person they were describing, even though since then he had changed. The judge called a lunch recess, and Ted watched Joanna conferring with her lawyer. He wondered if she, too, had changed, if there were two different people in this room than had been in that marriage, and what if they were attracted to each other, what if they met up now, as the people they were now—would they end up in this room?

Streep worked hard in the movie to make Joanna a sympathetic character. There was only so much she could do—by any stretch of the imagination, Joanna is a narcissistic monster who walks out on her child. But in Streep’s performance we at least feel her pain and conflicting motivations.

Corman’s Joanna just seems broken. When she abruptly gives up custody at the end, she stammers to Ted: “I guess I’m not a very together person. I guess . . . the things that made me leave are . . . still a part of me. I don’t have very good feelings about myself right now.”

Of course, the stakes of the custody arrangement are less steep in the movie than the book. Corman’s Ted is screwed, facing a court-determined regimen limited to Sunday afternoons with his son, and two weeks during the summer. Hoffman in the movie is looking at having Billy with him every other weekend and one night each week, and half of vacations—i.e., the familiar allowance for fathers today. With the custody arrangement being less wildly unfair to one parent, the movie can focus more on the emotional relationships involved.

When the film was being made, Hoffman was going through a divorce. Jaffe too was divorced. Interestingly, Benton, a Texan who made a success in the New York magazine world and once dated Gloria Steinem, was married in 1964 and never divorced. And Corman also married once, for thirty-seven years until the death of his wife.

Manhattan (1979)

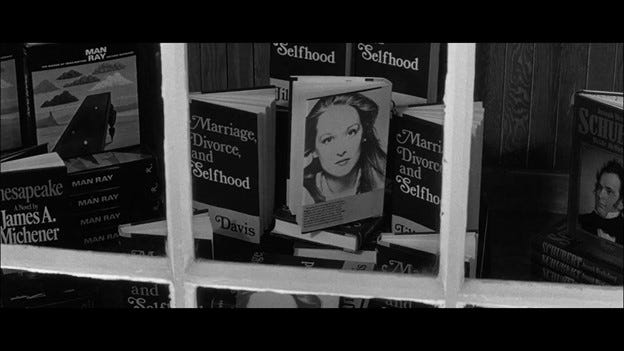

The same year as Kramer vs. Kramer, Streep would play Woody Allen’s ex-wife in Manhattan. The character is like a satire of Kramer vs. Kramer’s Joanna, the ex-wife as feminist nightmare: emotionally impervious, happily partnered with a woman, author of a bestselling tell-all about her unhappiness with her ex-husband. There is a great line when Woody’s new flame (Diane Keaton) tells him not to worry about his son being raised by a lesbian couple.

Keaton. They made some studies I read in one of the psychoanalytic quarterlies. You don’t need a male, I mean. Two mothers are absolutely fine.

Allen. Really? Because I always feel very few people survive one mother.

In this movie, there are also wordless father-son scenes, but they convey comic absurdity focused on the dad, not connection between parent and child. The boy (here named Willy, not Billy) wants an expensive toy; he and his dad play in a “Divorced Fathers and Sons” football league (the phrase is emblazoned on their shirts). The exception with spoken lines is when Woody takes his son to the Russian Tea Room and jokes that they might pick up women together. We are back in the territory of Kramer vs. Kramer, the book, not the movie.