DeMille's Divorce Films

Cecil B. DeMille and Gloria Swanson guide America "from Passion to Fashion"

Between 1918 and 1920, Cecil B. DeMille directed a number of films about married couples and their travails, most of them starring Gloria Swanson. In these films modern desires and the means to pursue them (at least for the wealthy) blow through—and sometimes down—the marital home.

“As for the influence of the Swanson-DeMille movies,” writes Hollywood stalwart Frances Marion in her memoirs, “they proved beyond doubt that women in this modern age must cast aside all the binding restrictions of the mid-Victorian era and become emancipated. How to achieve this complete freedom they were not quite sure, but they let themselves be guided from Passion to Fashion.” Marion’s rhyme nods to the mutual reinforcement of moral rebelliousness with the modern clothes, décor, and style epitomized by Swanson.

Three of the films feature divorce-and-remarriage plots. They begin with married couples “after the glow has worn off and the partners are growing bored with each other,” as Scott Eyman writes in his biography of DeMille. These films sympathetically portray the allure of a more attentive and exciting partner than one’s dull or complacent spouse.

Eyman observes that “DeMille was fascinated by the delicate emotional calibrations of romantic and erotic love and their trinity—marriage, temptation, infidelity.” At the time these movies were being made, DeMille’s marriage was sexless, and he was romantically involved with both Jeanie MacPherson, who wrote the screenplay for two of these films, and the actress Julia Faye, who appears in all three.

DeMille conducted his open marriage with tact and a clear understanding with his wife that, whatever his dalliances, she was his only true lifelong partner. It is not surprising, then, that DeMille’s divorce films “deal in a very cosmopolitan and modern way with realities that had always been swept under the rug in conventional Edwardian households.”

Indeed, while marriages are broken in these films, the institution of marriage is still presented as the vehicle for happiness. In two out of the three divorce movies, the divorced spouses are reunited with each other, and for the better. Divorce in these films is not necessarily tragic, and is even a means of correcting an inattentive spouse. The films teach that marriage can work but, to be successful in the long term, it requires (Eyman again) “tolerance, understanding, and a sense of humor,” and some effort “to stay sexually appealing to a partner.” An enduring marriage is not something to be relied on, but earned.

In the first of these movies, Old Wives For New (1918), Elliott Dexter plays Charles Murdock, a successful oil man who has been married to his wife Sophie (Sylvia Ashton) for many years. They have two adult children. Charles is still energetic and youthful, but his depressive wife has let herself go.

Charles craves the romantic connection they once shared. There is even a poignant flashback to the slimmer, more self-confident Sophie of years back. But the overweight Sophie of the present views marriage as a guaranteed lock on a spouse’s affections, which do not need to be cultivated or appreciated. In a telling scene, she is lying in bed, eating chocolates and reading the passage from the book of Genesis that proclaims husband and wife to be “one flesh.” She peremptorily orders Charles into bed, evidently not for anything fun, but rather as if he were a bedwarmer.

Starved for romance, Charles falls for Juliet (Florence Vidor), a New York fashion designer. (Clothes are important in these movies.) Sophie learns of Charles’s brief flirtation with Juliet, and tells him that she will never give him a divorce, while still treating him as an afterthought. Even their son and daughter are sympathetic to their father’s situation.

Things get a shake-up when Charles’s friend Berkeley, who “solves” the problem of marital unhappiness by having affairs, is shot by a jealous mistress (played by DeMille’s real-life lover, Julia Faye). The dying Berkeley asks Charles to cover up the scandal—with the result that Sophie, mistakenly believing that Juliet is involved, divorces her husband and accuses Juliet of murdering Berkeley. To protect Juliet’s reputation, Charles throws the press off the scent by traveling to Europe in the company of a different woman.

The now-divorced Sophie finds new love with one of Charles’s employees, who is able to support her in losing weight and feeling better about herself. Meanwhile, Juliet learns that Charles is not romantically involved with his travel companion; that it has been a ruse to protect her. Juliet and Charles are reunited in Venice. The movie ends with both Charles and Sophie happy with their new spouses.

Don’t Change Your Husband (1919) brings back a number of cast and crew from Old Wives For New, including MacPherson as scriptwriter, Elliott Dexter as the husband, and Julia Faye in the role of a mistress. But this time it is the husband who has let himself go.

“James Denby Porter,” the title card tells us, “through complete absorption in his business, has lost his Romance—and his Waistline.” Oblivious to his own inconsiderate habits and the toll they take on his wife Leila, James puts his feet on her sewing, lays down his cigar on her solitaire game, eats onions which she finds offensive on his breath. When he forgets their anniversary he tries to make it up after the fact—by writing her a check.

But the biggest difference from the previous movie is the addition of Gloria Swanson, “the vehicle through which DeMille would project an entirely unexpected vision—the postwar American woman, eager for emancipation and pleasure” (Eyman). Simultaneously relatable and arrestingly sexual, Swanson merged the worlds of upper-middle-class domesticity and exotic glamour.

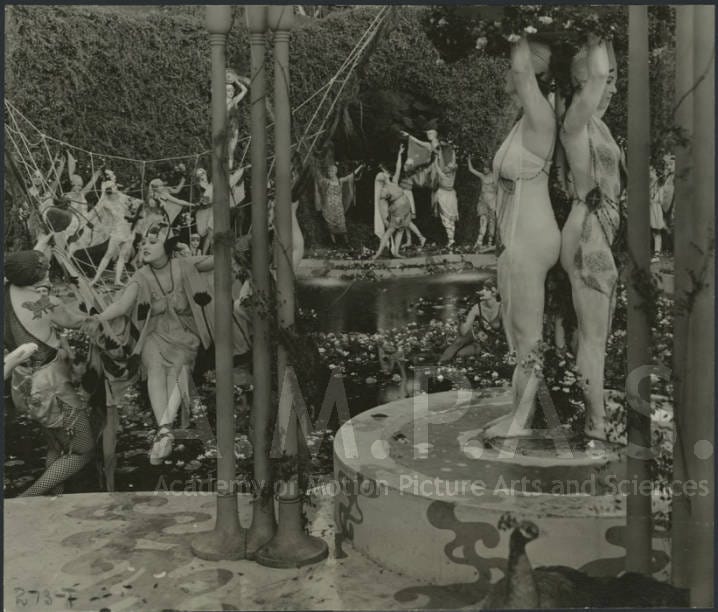

When the seductive cad Schuyler first sees Swanson as Leila, entertaining dinner guests in her chinoiserie, the camera follows his gaze, traveling the length of her body. In a striking fantasy sequence meant to represent Schuyler’s sweet-talking promises, we see Swanson swinging over a pool while nymphs dance, then regally enthroned on a platform borne by black servants.

After a sequence like that, small wonder that she divorces James, with his stained clothes and onion breath.

But divorce is what it takes for James to get himself into shape. He slims down, shaves his mustache (as he does in Old Wives For New, to make himself look more youthful), and advances in his career, all the while pining for Leila. When he next has the opportunity to dine with his ex-wife he arrives impeccably dressed, and behaves as a thoughtful gentleman in all ways. He even passes on the onions at dinner.

Leila, though, has married Schuyler, who turns out to be just as inconsiderate as her first husband had been, and moreover is having an affair with the trashy “Toodles” (Faye). James sees Schuyler out with Toodles, gambling away Leila’s jewelry, including the wedding ring James had given her. When confronted, the intoxicated Schuyler fires a pistol at James, but misses. Leila rushes to James’s side, and Schuyler, realizing he is defeated, leaves. James announces to Leila: “I’m going to wire for your same old suite—at Reno!”

Remarried, James and Leila are now attentive to each others’ dignity and comfort. The film’s opening scene is replayed, this time without cigar ash, onion breath, or forgetting of anniversaries. James still falls asleep in his chair, but Leila now finds it sweet. Meanwhile, we see Schuyler in a café, using his old pick-up speech on another woman.

The final film of the trio, Why Change Your Wife? (1920), opens with a rather sweet domestic scene of husband Robert (Thomas Meighan this time) and wife Beth (Swanson) in the bathroom. Robert tries to shave but is repeatedly interrupted by Beth making her toilette. None of this necessarily foreshadows marital problems, and there is even something endearing about Swanson asking Meighan to help fasten the back of her dress—an ancestor of the far more momentous marital un-fastening between Joel McCrea and Claudette Colbert in Preston Sturges’s Palm Beach Story.

But the problem soon becomes evident. Beth will not allow a space within their marriage for volupté. She complains about all of Robert’s pleasures—his wine cellar, his smoking, his taste in music, his dog. When he puts some sexy music on the phonograph—who can resist the “Hindustan Fox Trot”?—she changes it to something more staid. Robert purchases an elaborate negligee for her, but she ruins the effect with a dowdy slip, then berates him for wanting her to act like some “Turk.”

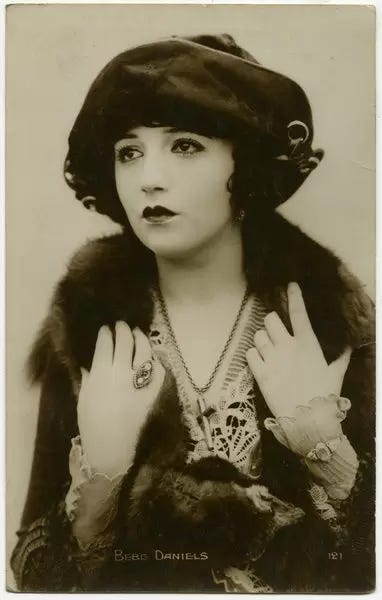

One of the models in the negligee shop, Sally (Bebe Daniels, an actress whose looks inhabit a pretty spot midway between Elizabeth Taylor and Julia Louise-Dreyfus), has long had a crush on Robert and is happy to seize what looks like an opportunity. When his wife refuses to go with him to a show for which he has purchased the tickets, he ends up taking Sally, and winds up back at her apartment afterwards. They kiss, before he is overcome with regret and leaves. Yet when his wife later smells the model’s perfume on him, she orders him out of the house—and throws out his film magazines. They are divorced, and Robert marries Sally.

As in Don’t Change Your Husband, the stuff on the other side turns out to be just more grass. Sally interrupts Robert’s shaving too, with annoying baby talk. She wants him to get rid of his dog. Things get interesting when she cajoles Robert into taking her to a fancy resort hotel, which happens to be where Beth is vacationing.

Swanson’s Beth has gone through some changes. On her first clothes shopping excursion after her divorce she overhears the shop girls gossiping about how it is no surprise her marriage didn’t work since she dresses so fustily. Determined to prove that she is no old stick, Beth orders her new outfits accordingly: “sleeveless, backless, transparent, indecent,” she says, “go the limit.” Thus when she shows up at the resort she is wearing her leg-exposing new bathing suit to the delight of the male guests.

But she is also more enamored of her ex-husband. She even likes his dog now. When Beth is accidentally locked out of her room, Robert helps her fasten her dress in back, which returns us to the opening scene of domestic irritation, transformed now into mutual yearning. To avoid temptation they each decide to leave the hotel early—and find themselves seated next to each other on the train back to the city.

Now things take an even more dramatic turn. Walking together as they leave the station, Robert slips—yes, on a banana peel—and cracks his head on the sidewalk. Beth takes him home, and the doctor says he must not be moved for 24 hours or he will die. Yet Sally arrives and insists on taking him away. There is a cat fight and, to protect the health of her ex-husband, Beth threatens to throw a bottle of acid in Sally’s face if she has him moved!

The two wives hold a tense vigil by Robert’s sickbed, Sally eventually falling asleep. The next day, Sally is determined to revenge herself. She grabs the bottle of acid and throws its contents in Beth’s face—discovering that, as Beth knew the whole time, it is only eye wash. Realizing she is defeated, Sally leaves, looking forward to the alimony following the impending divorce.

Beth and Robert remarry. Beth now flaunts the elaborate lingerie that had once embarrassed her. She even puts the “Hindustan Fox Trot” on the phonograph and dances with her husband. We end with a scene of the maid and butler returning the second twin bed back to the marital suite, and a title card that advises women: “if you would be your husband’s sweetheart, you simply must learn when to forget that you’re his wife.”