Call It Freedom and You Can't Have Everything

Two popular novels of 1937 about women and divorce.

This post isn’t directly connected with film. As part of my interest in divorce in American popular culture I have been reading more “middle-brow” novels than usual, and very much enjoying them as generally well-crafted books appealing to a broad middle-class audience of American readers. This reading carries me outside the academic and canonical-modernist constructions of twentieth-century American fiction, and I’m enjoying the view.[1]

So while last week I talked about a canonical American masterpiece, Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, this week I want to turn to two less illustrious novels, both published in 1937, that each look at the experience of divorce from the perspective of an upper-middle class white woman, one southern, the other Californian, in the 1930s.

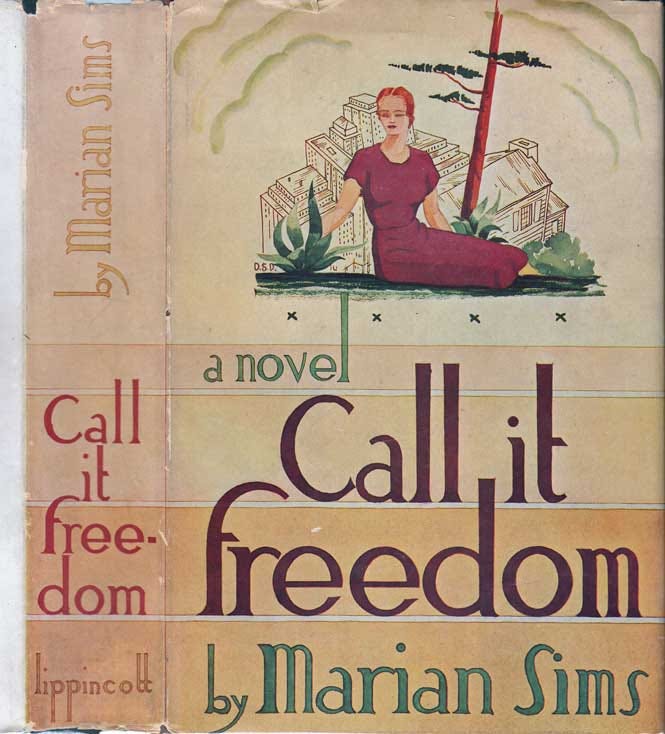

The first, Call It Freedom spent several weeks on the New York Times bestseller list in 1937. It was the third novel published by Marian Sims (1899-1961). Sims grew up in Georgia and, following her move to North Carolina, emerged as a successful if minor writer who published stories in popular American magazines such as Ladies’ Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post. To quote from her biography in the New Georgia Encyclopedia:

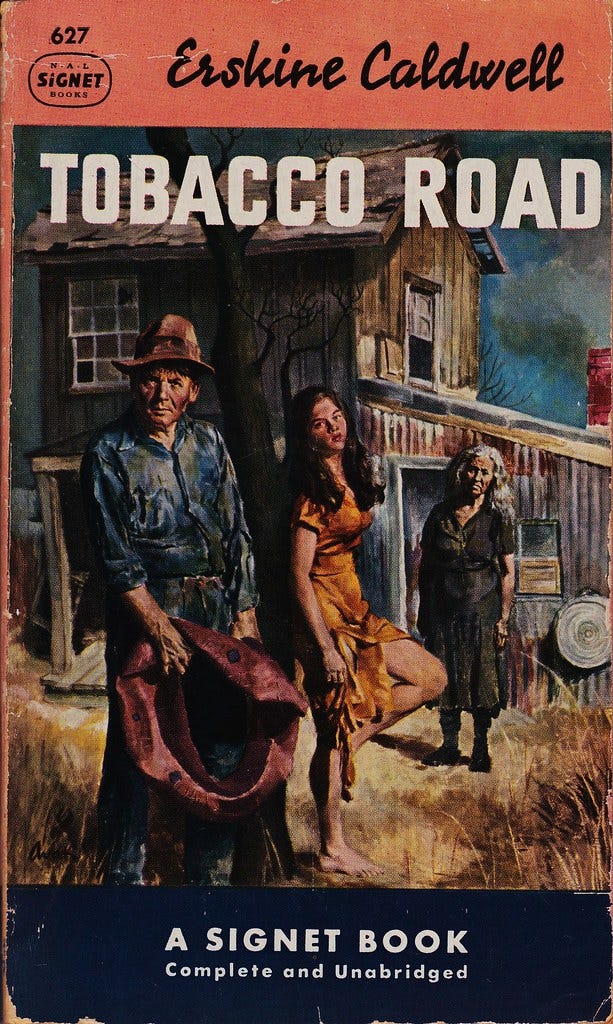

Much of Sims’s writing was motivated by a desire to provide an antidote to the work of southern writers like Lillian Smith and Erskine Caldwell, who emphasized what Sims called the “lurid” side of southern life. “Too much emphasis was being placed on share-croppers, Negroes, and backward-looking aristocrats,” she said, resulting in “a distorted picture of the region.” In her own fiction, Sims chose to depict her own social class of upper- and upper-middle-class whites.

This certainly applies to Call It Freedom. The novel’s protagonist is 34 year old Martha Harvey, who has just returned to North Carolina from Reno where she obtained a divorce from her alcoholic husband Ralph. Martha has custody of their eight year old son, and is financially provided for by her well-meaning if self-destructive ex.

The novel’s focus is not on any conflict between Martha and her ex-husband, or for that matter on any serious financial struggle to survive and provide for her son. Martha is comfortably middle-class. Her home is kept by Liza, a black maid who has long been with the family. Indeed, by the end of the novel a family inheritance leaves Martha entirely free from the need to work, though she takes a part-time job at a local bookstore as something to do.

Rather than focus on economic travail, or legal battles, or even much in the way of psychic distress, the novel’s goal is to explore the social situation of an educated, middle-class, divorced woman in the mid-1930s. Sims and her intelligent protagonist convey all the subtle dynamics of a woman uncertain about her new social status.

Martha has a group of friends, nearly all of them married couples. Now unattached, Martha’s social life depends on her not becoming a burden to her friends—or a threat. The rounds of golf, the bridge and poker games, the drinking—so much drinking (it’s a wonder Martha’s ex is the only alcoholic in the book)!—are customarily organized in pairs. Loneliness is a constant struggle for the new divorcee, social abandonment a constant anxiety. It does not help when she begins to fall in love with one of the husbands in the group.

Another challenge for Martha as a single woman is, well, horniness, put a bit more indirectly, though honestly, in the book. The novel deals with Martha’s conundrum of how to address her sexual needs, a conundrum at one point incarnate in a handsome bachelor who is more than willing to sleep with her.

She is tempted. But in the social world anatomized by Sims, the expectation that sex is confined to marriage cannot be abandoned without significant moral and psychic consequences. This dimension of the book may be hard to parse for the contemporary reader, but is important as it probes with keen awareness the costs our culture has already paid from the standpoint of a character and society who have not (yet) gone down our road.

Call It Freedom very much presents itself as a novel of the South. As mentioned above, Sims was concerned to write about the educated, white, middle-class, liberal (or at least liberalizing) segment of the South, as opposed to more familiar representations of the South in 1930s popular culture as a land of hillbillies (e.g., Al Capp’s comic strip Li’l Abner, begun in 1934) and dirt-poor grotesques (e.g., Erskine Caldwell’s 1932 novel Tobacco Road).

In a meta-fictional moment, Martha praises the draft of a Southern novel her friend Dave is writing about their educated and mannered set. “I’m tired of swamp-dwellers and perverts,” she tells him, “it’s time somebody wrote about you and me and our kind.”

Sims not only holds a brief for middle-class characters, but for the value of the middlebrow novel. Call It Freedom voices criticism of the plethora of book clubs that bow to the “publishers’ lists, choosing dull and ‘important’ books that few of them would ever read.” This kind of American literary consumer, we are told, “preferred an important book on the living-room table—unopened—to a lesser author who had not assimilated the fact that genius and a painstaking verbosity were the Siamese twins of the nineteen-thirties.” It may be an irony that the particular novel referred to here is likely Hervey Allen’s 1933 critical darling Anthony Adverse, which today is hardly more known than Call It Freedom.

Sims’s comments above may seem a bit resentful, yet the fact is that Call It Freedom is a welcoming, intelligent reading experience and an illuminating sociological map of its particular territory, probably more informative as to changing American mores in the 1930s than, say, a Southern gothic by Faulkner. Faulkner, as far as I know, never wrote about Jell-O salad.

Of course, the book has its limitations. Too often Sims delivers her critiques of aspects of Southern society in the form of set speeches mouthed by her characters. These speeches, moreover, all tend toward the same kind of tendentiously bien pensant liberalism that would reach its popular apogee in To Kill A Mockingbird.

Race is treated with a mix of Southern familiarity and progressive paternalism. I don’t feel confident I can always gauge what is accurate depiction, what misrepresentation, and what critique.

The book describes a milieu where characters are wont to compliment each other by saying “that’s white of you.” The black housekeeper Liza is portrayed with a fond familiarity that borders on the patronizing. A white character’s upright moral quality is indexed by his deploring a lynching of what he describes as “a pitiful black savage.” Martha goes on a philanthropic spree at Christmastime and tells the welfare agency “I’d rather have a Negro family than a white one,” to which the case worker replies: “Yes, there’s a lot more satisfaction in helping them. They’re pitifully grateful for whatever you give them, while most of the whites take it as a matter of course and complain about what you don’t give ‘em.”

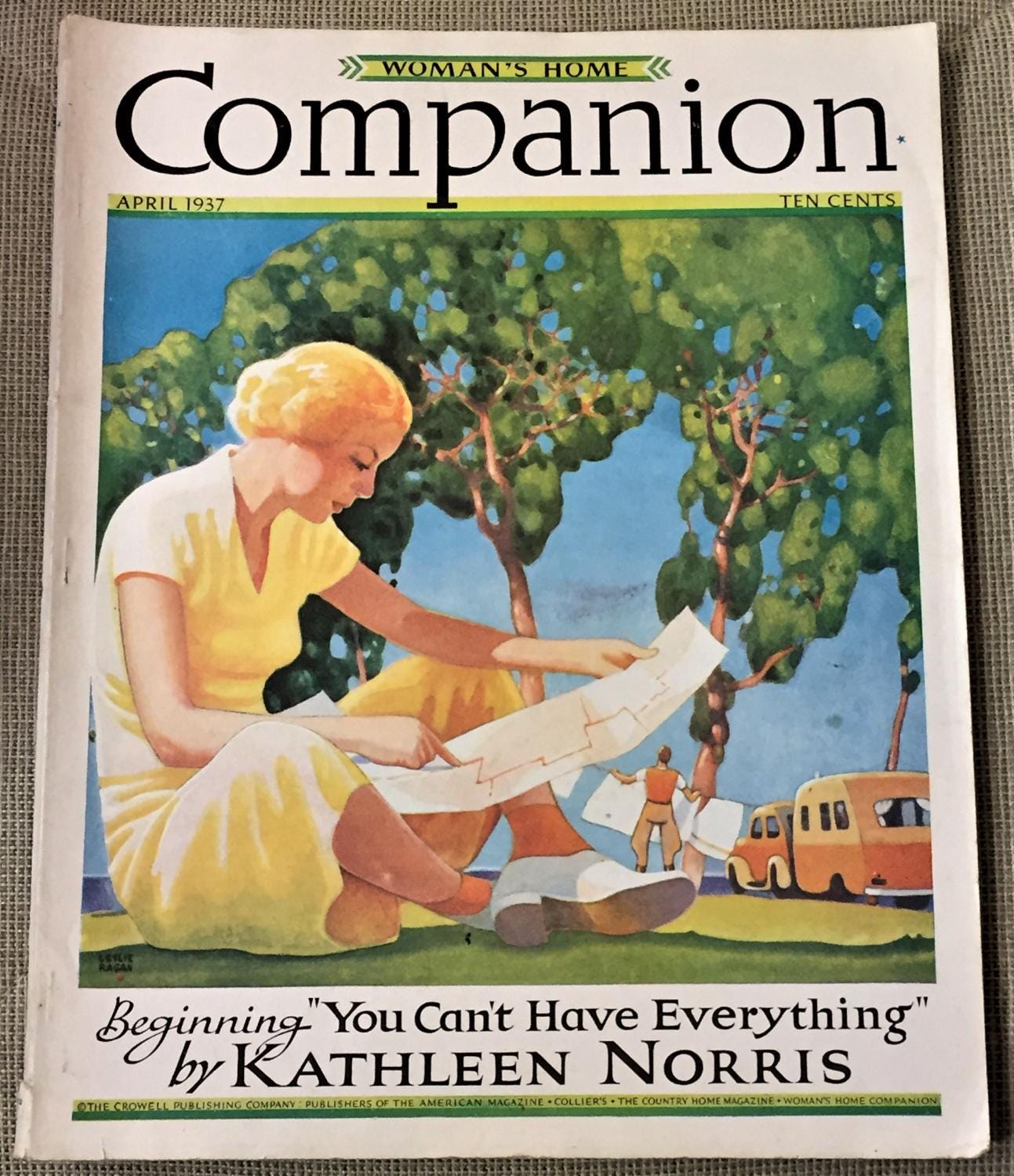

The second book I want to consider here is You Can’t Have Everything by Kathleen Norris. Norris (1880-1966) is the epitome of the forgotten middle-brow novelist, one of the best-selling American authors of all time but hardly known today. Norris published over 90 novels, more than a dozen of which were adapted for film. A Catholic, Norris is usually referred to, when she is referred to, as a popular writer who emphasized domestic virtues and family life in her fictions.

In You Can’t Have Everything, Mary “Cam” Campbell, mother of two little girls, is miserable in her marriage to Bob Sylvester. A former Stanford football player and doting suitor, Bob is now all business, and has been for some years, since the Stock Market Crash that determined him to focus all his energy on rebuilding the household egg. He ignores his wife, has them sleep in separate rooms, and lives his entire social life away from her, not out of malice but because he has come to see her as a dependable fixture in their home that will be there when he comes and goes. Despite her attempts to win back his attention, their love is dead. But after all, they’re an old couple: he is 30, and she in her 20s.

Everything changes when Cam meets her dream man. The widowed John Kilgarif is a renowned author; Cam has long admired his work. John falls hard for Cam, courts her as best he can in her husband’s long absences, and Cam finally realizes she has to be free of her marriage. Bob is glum, but understands he is in the wrong, and they divorce. Cam, as the mother, has custody of the girls, but agrees to visitations with their father.

Remarried to John, Cam’s life is a fantasy of literary parties and exciting travel. John brings her to a White House dinner. They even climb partway up Everest together.

The only problem is that John is kind of a psychopath. During their courtship he was constantly solicitous of Cam’s girls, and he has a young son from his first marriage. But John is bizarrely jealous of anything that takes Cam’s attention away from him, including their three children. He is content to let servants care for the children at home, and always proposes jaunts away without the kids. Cam passively gives in to his every proposal for weeks- and months-long trips away from their children (Cam’s girls are only 4 and 6), beginning with a two-month honeymoon. It is only when, at the end of the novel, a medical crisis puts his son’s life in danger that he does a complete turnaround and becomes a competent father and sane husband.

You Can’t Have Everything is the first book I have read by Norris, and so I can’t say how typical it is of her oeuvre. Norris evidently draws on some biographical experience. Cam becomes a writer alongside John, just as Norris’s writing career was encouraged by her husband Charles, a novelist and the brother of the better-known writer Frank Norris. She also raised her late sister’s children after their father remarried, and so must have had some sense of uncertain family arrangements.

Comparing it to Call It Freedom, You Can’t Have Everything similarly gives us a first marriage that fails due to the husband, a writer waiting for the chance to be husband number two, and a set of challenges for its middle- or upper-middle-class female protagonists that are at least partially alleviated by hired help, to an extent in the case of Norris’s novel and much wealthier heroine that sometimes seems unintentionally comic. With nurses to mind the children and maids to cook and clean, we are nevertheless told that Cam “took charge of the luncheon, pouring milk, seeing that the sandwiches were distributed.” Way to take charge, Cam!

You Can’t Have Everything is more sentimental and demure than Call It Freedom, and certainly less socially detailed. Cam and John, like Norris and her husband, live on a ranch in California, not in Southern urban society. Sims’s Martha is vivid and wily, and her internal life engagingly intelligent, more so than Cam’s, who takes upon herself all of her conflicts with her new husband, and whose daughters are porcelain dolls in comparison with Martha’s very real little boy. Call It Freedom is by far the better book.

Yet both books register an appropriately complex and uneasy set of attitudes toward the reality of divorce for middle-class women, not least in the happy if if not entirely convincing endings of each. Norris makes John extremely icky in his jealousy of his wife’s children (“They don’t love you the way I love you,” he tells Cam when she soothes her four year old who had a nightmare). Then she reinvents him in the final pages as a contrite and model dad. Divorce, and its impact on children and the family, are framed in Norris’s novel as a choice that, while perhaps understandable, requires lifelong atonement. As Cam reflects in the final chapter:

She must always pay for the choice she had made; now and in the year to come her daughters would be less her own because she had taken them away from their father. They would grow to beauty and understanding, and they would go to him for weeks at a time, for contacts of which their mother would know nothing, and they would come back, bound to be silent about them, bound to seem to sympathize with her in what she had done, just as they showed him sympathy and kindness when they were with him. Yet all that only made her daughters dearer. Even mistakes and stupidities had their gain.

Moreover, Cam’s ex-husband has also become an attentive father to their daughters and a good husband to his second wife. One wonders if Norris thought that Cam should have given Bob another chance.

Sims, on the other hand, lets us accompany her Martha through a year of divorced life and singledom. Having overcome or at least managed various social challenges and romantic temptations, Martha can announce: “I think I’ve learned to stand alone.” That, at least, is what she tells her friend Dave, the writer, when in the final pages he asks her to marry him.

This is no second-wave feminist declaration of fishes and bicycles, though. It becomes clear enough that she and Dave will marry, in another six months. This brief delay, and the mildly anti-establishment touches (Dave is a writer, Martha is on her way to becoming a book reviewer) do not alter what is ultimately a conventional plot in which a virtuous woman resists two wrong suitors to be rewarded with the third, right one. Divorced life is hard, the novel shows, but it can be done well or poorly. And even mistakes and stupidities have their gain.

[1] I don’t have my copy of Gordon Hutner’s excellent What America Read: Taste, Class, and the Novel, 1920-1960 with me or I’m sure I would quote from it here. It’s one of the studies of American middle class fiction I’ve read recently that I have found inspiring, and it has brought me to a number of interesting writers, often women, who hit the best-seller lists and won awards in their day but are largely unknown now. (Ursula Parrott is one such.) These writers are in many ways a more telling index than canonical English Department favorites are to popular American attitudes and transformations experienced, at least by an American middle class readership.