All The Lonely People

Divorce Starts To Become A World Of Its Own, 1959 – 1964

Divorce, as we have seen, is hardly uncommon as a plot element in American film. Indeed, it is a major engine for conflict and resolution in films from the silents on, sometimes melodramatic and often comic. When one detects hesitation about the portrayal of divorce in film it comes with World War Two and the war’s aftermath, signaling anxieties about the new spike in divorce rates, the phenomenon of wartime marriage and its aftermath, the far-reaching upheavals in American social relations, and the palpable confusion that characterizes much of the 1950s as to how and whether American society might recover a (rather illusory) sense of prewar stability.

Divorce as a major plot element becomes rarer in the 1950s than it had been before the war, and its comic dimension more clumsy and strained. At the same time, we see the incrementally growing indications of divorce portrayed as something neither comic nor tragic, but a state of adult life on its own. There is at least more of a narrative suspension allowing for some consideration of the state of divorce before its resolution through a new marriage or reunion with the former spouse. The real pathbreaker in this regard actually precedes the 1950s by two decades: The Divorcée (1930) with Norma Shearer explores the sexually promiscuous and emotionally miserable state of the main character as a divorced woman, before it reunites her with her husband in the final seconds. But that exception aside, this state of post-marriage not primarily as a problem to be solved but as a condition to be explored starts to bubble up, tentatively, toward the end of the 1950s.[1]

From the end of the second Eisenhower term into the Kennedy administration we get a half dozen movies that seem to map out, more fully than has been seen in American film before, the territory of divorce on something like its own terms. This is not yet anything like the developed divorce movie of, say, Paul Mazursky’s An Unmarried Woman (1978). Yet these movies just begin to enter a different world than the safe and structured interruptions of marriage, whether comic or tragic, of previous films. Divorce World.

What is this world like? It is an often sad place, peopled by characters who are lost, lonely, grateful for small moments of tenderness and prepared for their quick vanishing. It is a serious place: several of these films are based on stage plays and bring the atmosphere of stark realism, highbrow stagecraft, and a kind of forlorn urban poetry. And it is a beautiful place. These films’ black and white photography is achingly luminous, a breathtaking visual swan song prior to the final abandonment of black and white film by Hollywood in the second half of the 1960s.

Middle of the Night (1959)

Paddy Chayefsky adapted the screenplay from his successful Broadway play about a pretty, divorced secretary who accepts the attentions of a well-off Jewish widower more than three decades her senior. The stage production with Gena Rowlands and Edgar G. Robinson must have been something to see. In the movie, the older man is a tired Fredric March, not bad in his role, while the young woman is a very miscast and panicked-seeming Kim Novak. The New York City footage is gritty and compelling, and Lee Philips, onscreen for two minutes as Novak’s ex-husband, is great.

Chayefsky’s screenplay is a grim farce of Curb Your Enthusiasm awkwardness, and the film only intermittently achieves the necessary timing to make it work. Reviewers who saw both play and film noticed the diminishment of the requisite ethnic Jewishness in the latter. Accents, like the casting, don’t always make sense. But, intentionally or unintentionally, this may be the film’s most interesting subtext: how Hollywood (unlike Broadway) struggles to display Jewishness at this time, in this case with a relationship between an older Jewish businessman and a young Gentile starlet.

The Savage Eye (1960)

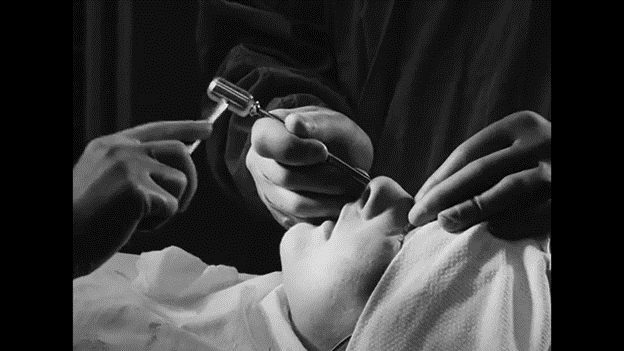

An independent and experimental film, The Savage Eye was directed by Joseph Strick, Ben Maddow, and Sidney Meyers, driven initially by an impulse to transplant the grotesquery and social critique of Hogarth from the painter’s eighteenth-century London to a contemporary American city. Los Angeles became the target and, over several years, footage was assembled from such camera eyes as Haskell Wexler, Helen Levitt, and Max Yavnow. (This seems to be a very Jewish production.) In terms of photography, the film is extraordinary: an artistic and arresting look at seedy, seamy Los Angeles: the operating room of a plastic surgeon, a pet cemetery, roller derby, burlesque show, Pentecostal church, pro wrestling match, drag bar, etc.

A sampling of images from the film:

There is a growing sense of slumming contempt on the part of the filmmakers towards their subject. A 1960 review remarked of the filmmakers: “They did not like what they saw and expressed little compassion for the human beings they photographed.” One can’t help but be reminded of Diane Arbus, developing her career outside of commercial photography at the time.

The filmmakers attempt to organize their material with a flimsy plot about a woman who moves to Los Angeles while waiting for her divorce to finalize. A conversation between her and an all-seeing figure credited as “The Poet” is conducted by voiceover—and is an annoying impertinence, as the male figure delivers pseudo-Gallic drivel about Man and Society: “The world is divided into two classes: those who are alive and those who are afraid.” “Salesmen of our own illusions, attached to a green planet by the soles of our feet.”

Divorce here is a consignment to the soulless streets and dive bars of modern America. “Half the women in this house live on bourbon, cottage cheese, and alimony,” says the woman of her rented bungalow. “Even the cat is divorced.” In this, the film’s vision is no advance on over a decade of film noir, and not nearly as insightful a portrait of 1950s Los Angeles as Ross Macdonald’s “Lew Archer” novels. Still, the footage is tremendous and, under the avant-garde pretensions of the directors and their script, a city flexes its animal muscles.

The Misfits (1961)

Arthur Miller wrote the screenplay for his then-wife Marilyn Monroe (they would divorce the year the movie was released) and John Huston directed. We begin with Monroe on her way to the courthouse for a Reno divorce; she afterwards decides not to toss her ring into the Truckee. She quickly meets up with Eli Wallach, Clark Gable, and Montgomery Clift, and shacks up with Gable. Yet this still has the makings of a divorce movie, with Monroe wanting to know why people fall out of love, why their love doesn’t make them happy.

She researches. Wallach’s wife died, but Monroe learns that he never danced with her when she was alive, though he is a great dancer. Gable’s ex-wife cheated on him: “In those days I thought you got married and that was it. But nothing’s it. Not forever.” Monroe: “That’s what I can’t get used to. Everything keeps changing.”

At the end, Gable tames a wild horse, and Monroe tames Gable, bringing him around to her value of compassion rather than control. Wallach embodies a false compassion; he is not man enough to be truly brutal or truly compassionate. The naturally compassionate Clift was the alternative to Gable, but he takes his leave from the story. Gable becomes compassionate by virtue of his conscious decision to lay aside his brutality. This is all plausible, though it mars what is otherwise a masterpiece of a film, one that should not have ended happily.

Two For the See-Saw (1962)

Another adaptation of a stage play, this movie stars Robert Mitchum as a lawyer recently moved to New York City after separating from his wife, and who finds solace in the bed of Shirley MacLaine, playing a kindhearted Jewish bohemian named Gittel Mosca (short for Moskowitz). This is another instance of the expanded yet still uncertain portrayal of Jewish ethnicity in Hollywood movies, and an example of the heartland Gentile – urban Jew romantic pairing.

In this case, Mitchum is miscast, entirely too tough and intimidating to work as a forlorn and ego-bruised fish out of water. In the stage play by William Gibson, Henry Fonda played the lead alongside Anne Bancroft. Nevertheless, it is enjoyable to watch Mitchum and MacLaine, and even more enjoyable to behold New York City via Ted D. McCord’s coruscating and textured photography.

While the movie immediately puts Mitchum in relationship with MacLaine, and returns him to Nebraska at the end, this is still, like The Misfits, a post-marital movie that opens out on uncertain social and emotional vistas.

One Potato Two Potato (1964)

Groundbreaking in terms of theme, this movie centers on an interracial romance and marriage between white divorcée and single mother Barbara Barrie and her black co-worker played by Bernie Hamilton. Barrie’s absentee husband returns to demand sole custody of their young daughter, whom he cannot bear to be raised in a black family. The movie is framed by the court case, the judge delivering the awful verdict at the end.

Directed by Larry Peerce, the movie is uneven in performance though consistently moving and beautifully filmed by Andrew Laszlo. Barrie is superb, and so is the daughter (who would go on to work as part of the directorial crew on Twin Peaks). The uncertain and yearning courtship provides the best scenes until that of the devastating finale.

The Private Lives of Adam and Eve (1960)

Of course, not every black and white movie from this period with divorce in the plot is a gem. The Private Lives of Adam and Eve is an amateurish, low-budget romp in which an unhappy wife on her way to get a divorce from her husband turns out, in a long dream sequence, to be Eve, just as her husband is Adam, with Satan (Mickey Rooney) and Lilith (Fay Spain) tempting them in ways all couples must contend with ever since Eden. The film seems like it was written and filmed in a day, with plenty of hokey sex jokes. It’s so lame as to be hard to watch, but how many movies have Mickey Rooney, Mamie Van Doren, Tuesday Weld, Mel Tormé, and Paul Anka? The opening song by Anka is catchy, at least.

Meanwhile, in color…

Strangers When We Meet (1960) is not a divorce movie, but is still worth mentioning because it suggests how fragile are the marital bonds in the suburban California landscape it portrays. Kim Novak, so miscast in Middle of the Night, is absolutely riveting here. Her fascinating performance, subtle and raw, of an unhappy wife who has an affair with a married architect (Kirk Douglas), eclipses everything and everyone around her (including Walter Matthau and Ernie Kovacs).

Mervin Le Roy directed Mary Mary (1963), another attempt to reheat the freezer-burned comedy of remarriage without the social context and cinematic wit that made that genre so brilliant in the 1930s and early 40s. Debbie Reynolds is fine, but the movie is forgettable.

The real opposite—psychologically, cinematically, culturally—to the sad, serious, black and white forays into Divorce World, though, is McLintock! (1963). John Wayne shows wife Maureen O’Hara how a real man handles a demand for a divorce when, at the end of this western, he throws his wife over his knee and paddles her in front of the entire, wildly cheering town. Naturally, when he rides off in his buggy she runs after him, properly tamed.

And yet, the best movie about divorce of this whole period is a color movie: Disney’s 1961 The Parent Trap. I have discussed its mythic strangeness and insights elsewhere.

The Soundtrack

Finally, take as another gauge of the culture the string of hits by lyricist Hal David and composer Burt Bacharach that included 1962’s “Make It Easy On Yourself” (sung by Jerry Butler) and, in 1963, such David-Bacharach compositions as “Anyone Who Had A Heart” (Dionne Warwick), “Twenty Four Hours From Tulsa” (Gene Pitney), and “Wives and Lovers” (Jack Jones), followed by “I Just Don’t Know What To Do With Myself” (Dusty Springfield’s version charted in 1964), “A House Is Not A Home” (Warwick), “One Less Bell To Answer” (Keely Smith), and more.

Some samples:

If you really love him

And there's nothing I can do

Don't try to spare my feelings

Just tell me that we're through.--“Make It Easy On Yourself”

You couldn't really have a heart

And hurt me like you hurt me

And be so untrue

What am I to do?--“Anyone Who Had A Heart”

I hate to do this to you

But I love somebody new

What can I do

And I can never never never go home again.--“Twenty Four Hourse From Tulsa”

Don't think because

There's a ring on your finger

You needn't try any more.For wives should always be lovers, too.

Run to his arms the moment he comes home to you.

I'm warning you.Day after day

There are girls at the office

And men will always be men

Don't send him off

With your hair still in curlers

You may not see him again.--“Wives and Lovers”

One less bell to answer

One less egg to fry

One less man to pick up after

I should be happy

But all I do is cry.--“One Less Bell To Answer”

In a 1999 New York Review of Books essay on Bacharach, Geoffrey O’Brien wrote that David’s lyrics conjured

a world of rainy days and breakups and telephones, airports and doorbells, makeup and taxis, “an empty tube of toothpaste and a half-filled cup of coffee”: and, unmentioned, booze and Valium and cigarettes, therapists and exercise programs, broken glass, hours of silence and immobility, crowded bars and dates gone sour.

Welcome to Divorce World.

[1] As discussed in an earlier post, the year 1956 gives us the twice-divorced title character of Hilda Crane who, though quickly married once again, first articulates her questions about the best path for her as a college-educated woman, questions that are not resolved with her remarriage. The same year also gives us the two leads in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, both divorced, and who do not seem in a rush to get married even before they are distracted by an alien invasion.